Loading the page ...

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

(1780 Montauban – 1867 Paris)

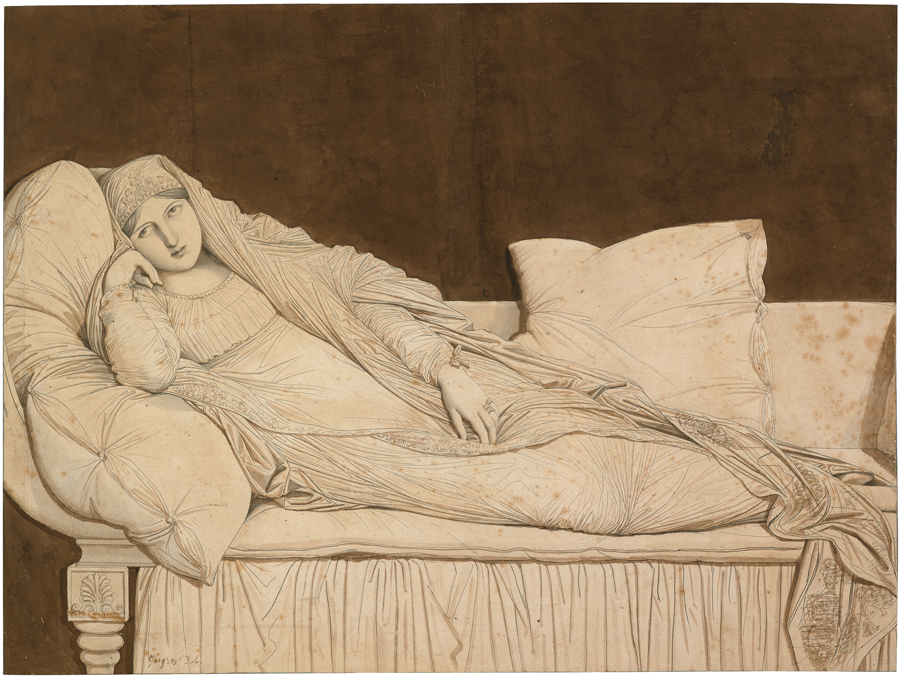

Full-length Portrait of Lady Jane Montagu reclining on an antique chaise longue. Etching, silhouetted, extensively reworked with pencil and brush and brown wash. 34.7 x 46.3 cm. Signed: "Ingres Del".

The genesis of this unique work of art – a symbiosis of etching and drawing – is as enigmatic as the gaze of the lovely Lady Jane Montagu whom Ingres has immortalized. This is the only known impression of this etching, which has not been described either by Delteil or by H. Schwarz ("Ingres Graveur", Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Paris 1959, pp. 329–342). We know little of Ingres’ activity as a printmaker. Apart from a small number of lithographs by his own hand, only one etching by the artist is known to exist: the Portrait of the Archbishop Gabriel Cortois de Pressigny, which was done in Rome in 1816 (Delteil 1, ill. p. 59). Although this print is generally accepted today as an autograph work, the doubts concerning its authorship have never been completely laid to rest. In his preface to the volume on Ingres in the Inventaire du Fonds Français Jean Adhémar speculated that this portrait might not be by Ingres at all. According to Adhémar it is hard to see how such a technically accomplished print could be a first attempt by someone new to the medium. The author of the portrait might therefore very well be the engraver Claude-Marie-François Dien (1787–1865), who was a friend of Ingres and lived in Rome at the same time. But one can just as well imagine that Ingres produced this tyro effort under the direct guidance of his friend and colleague. Quite apart from this problem it has to be said that our Portrait of Lady Jane Montagu shows startling stylistic parallels with the bishop’s portrait. The folds and shaded areas of the clothing are rendered with similarly simple, light parallel hatchings and deftly drawn lines. Both portraits are executed in a very light and transparent technique. The stylistic analogies are mainly evident in the neatness of the floral adornments on the sleeves and garment of the church dignitary, as well as on the headdress and seam of the young woman’s veil (ill. p. 61). It is therefore not implausible that both works might be by the same author.

The Lady Jane Montagu of the portrait was the daughter of William Montagu, 5th Duke of Manchester, and Lady Susan Gordon. Almost nothing is known about the life of this young noblewoman, who died in 1815 at the age of only twenty-one (see H. Naef, Die Bildniszeichnungen von J.-A.-D. Ingres, Bern 1978, Vol. II, p. 5ff). Several preparatory drawings by Ingres of a tomb for Lady Jane Montagu have been preserved. It is not clear whether Ingres did in fact receive a commission to design a monument or whether his imagery was inspired by classical and Renaissance prototypes. The Musée Ingres in Montauban preserves a total of seven study sheets, including a large and very detailed drawing in watercolor dated 1860 (see G. Vigne, Dessins d’Ingres. Catalogue raisonné des dessins du musée de Montauban, Paris 1995, nos. 2578–2585). Another large and highly fi nished drawing is now kept in the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. This drawing, dating from 1816 and executed in pen and brown ink with ochre and brown wash, displays a serene and elegant classicism which comes very close to our version (see exhibition catalogue Ingres. In Pursuit of Perfection. The Art of J.-A.-D. Ingres, Louisville-Fort Worth 1984, pp. 100–101, no. 36, p. 187). In contrast to our sheet, however, the composition is framed by two Corinthian pilasters and a curtain on both sides, while behind Lady Jane Montagu’s daybed stands an antique candelabra, and the rear wall appears more elaborate by the addition of panelling (ill. p. 65). In its horizontal format and compositional focus on the figure of the reclining woman the Melbourne version differs radically from the watercolor in Montauban (Vigne no. 2584). Here the artist’s attention is directed mainly at the exact rendering of the architecture of a sculpted tomb, prototypes of which date to the Early Italian Renaissance. Ingres has chosen an upright format for this purpose and enriched the portrayal with numerous additional details. In keeping with the traditional symbolism of mortality two genies are closing a curtain, and the richly ornate architecture framing the tomb is depicted with great precision. In contrast to the earlier version the architectural context makes the figure of the deceased seem smaller and even gives her facial expression a more distant and impersonal look (ill. p. 63).

For the present work Ingres had carefully cut out the etching produced either by himself or an artist closely associated with him and stuck it onto a larger sheet of paper, which served as a neutral background and was entirely covered with a broad area of opaque brown wash. The artist then carefully reworked the portrait by means of single sharp pencil lines and delicate brushwork in different shades of brown. The effi ciency of his method is impressive. With great economy of means Ingres’ delicate brush technique creates a maximum of atmospheric and chiaroscuro effects and makes the scene appear in a soft light. Masterfully Ingres has succeeded, for instance, in rendering the drapery under the chaise longue in an amost tactile way. The materiality of the objects and clothing is brought out by the differences in texture: one can feel the softness of the large cushion and the fine pleats of the young woman’s garment and long cloak as she looks the beholder directly in the eyes with a melancholy, dreamy gaze, her beautiful and even-featured face resting on her right hand. Lady Jane seems turned in on herself, as though she were already looking into another world. The technical procedure employed by Ingres is far from unique in his oeuvre. Ingres was a tirelessly creative artist who was always experimenting and searching for the ultimate artistic formulation. Several examples are known of Ingres using pencil and brush to rework prints done by himself or others. The famous Group Portrait of the Gatteaux Family from the year 1850 is another specimen of a synthesis of print and drawing. In this very case Ingres based himself on reproductive engravings by the same Claude-Marie-François Dien after his own portrait drawings, which he carefully cut out along the contours, stuck onto pasteboard and reworked in pencil, before integrating them in a larger composition (see exhibition catalogue Goya bis Picasso. Meisterwerke der Sammlung Jan Krugier und Marie-Anne Krugier Poniatowski, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna 2005, pp. 48–49). A stylistic comparison with the slightly larger drawing in Melbourne gives useful information concerning he chronology of the present work. In contrast to that version, where the day bed is richly ornamented with lotus palms and the cushions and materials have detailed decorative patterns, our sheet is characterized by a more severe and purist approach. All ornamental details have been deliberately dispensed with so as to focus the beholder’s attention entirely on the pensive young woman. Her pose matches that of the Melbourne version almost exactly, except that the book in Lady Jane’s right hand is missing here. It therefore seems likely that our composition represents an earlier stage of development, directly preceding the Melbourne version. The portrait casts an irresistible spell on the beholder. Despite the mood of silent meditation the scene still radiates an almost stirring inner tension. This dialectic is intrinsic to all great art. With impressive sureness of touch Ingres has created an intimate and moving masterpiece of timeless beauty.

From the estate of Hans Naef (1920–2000), author of the catalogue raisonné of Ingres’ portrait drawings.

Contact us for further information